Slavery Plays Jump-Rope with Racism: Examining the Poetry of Phillis Wheatley

By

2009, Vol. 1 No. 12 | pg. 1/1

KEYWORDS:

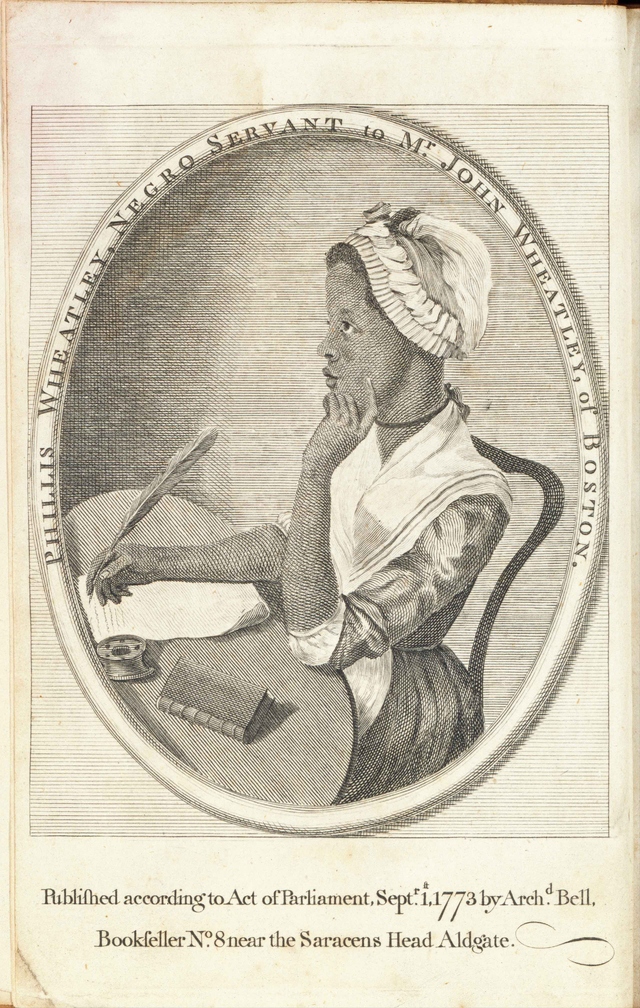

Children’s literature in the context of this research paper (and hopefully too in the eyes of the majority) is the ultimate escape; it is neither box nor leash nor constraint of any sort. It is the one genre of literature that does not hold itself to a predetermined standard upon which the postmodern (as in the theory, not as in the time) minds can muddle together an amalgamation of text to form something novel. It is a genre of literature in which we look upon ourselves and our own childhood imaginations for inspiration. As such it is capable of taking us to the most beautiful places we could never imagine and so too can the pages turn as equally dark. Marilyn Nelson creates A Wreath for Emmett Till almost two hundred years after Phillis Wheatley yet somehow they deal with the darkness engulfing their respective social arenas in a similar fashion. Form plays a very important role in the life of Wheatley wherein her freedom in slavery had become a meter of constraint, so too does Nelson deal with the murder of Emmett Till, using form to adequately convey this raw set of emotions to an audience of young adults. Before I jump in to the bond that these two women share in their understanding of poetry and its relevance to their issues, allow me to introduce Wheatley and the circumstances that led to her influence Nelson. Phillis Wheatley’s legacy is one shrouded behind the veil of slavery in the 18th Century. Her contributions to literature and the movement to abolish slavery might as well have been anonymous in that the academic world has never settled on the matter of where Wheatley’s allegiances lie in relation to the social issues of her time. Wheatley’s position in literature is a complex and entirely unique one as no other African American, female poet has mastered the classic art of lyric verse in an era that hosted slavery and sought to keep women on the outskirts of the social spectrum. In order for Wheatley to have captured an audience in this age, every aspect of her unlikely journey had to have been flawlessly aligned: from the compassion and ease of life that her masters provided for her, to their willingness to allow her to read classic poetry, even too is her own dedication to this mission important. Wheatley’s poetry specifically targets the widely important social issues of her time such as slavery, and religion—however, the question that wanders in the back of all of her readers’ minds has always been with the sincerity with which she wrote poetry. Many critics and poets alike have been divided over the ages as to Wheatley’s understanding of the situation she was placed into and the position she held as the first African American female poet. We will attempt to bridge the gap from the truth, or allusion to truth, in Wheatley’s poetry and how it has evolved to influence later literary movements. As such we will also explore Marilyn Nelson’s A Wreath for Emmett Till and how this work draws upon the blueprint that Wheatley set forth so many years before. To do so, we’ll take a look at Wheatley’s own poetry and her personal letters. In recreating the psyche and drive behind Wheatley’s work, I the hope to juxtapose it with Nelson’s own process behind the creation of her own work, particularly regarding A Wreath for Emmett Till. Critical analyses of Wheatley’s work will be referenced as a secondary resort in order to explore her place in literary academia and her contributions to other literary movements as it relates to the children’s literature genre. Much like the pressures that rest on the shoulders of many children’s literature writers, Wheatley was well aware of the pressures rested upon her shoulders as a female African American poet and though her poetry exalt the likes of such men as George Whitefield and George Washington, she equally understood that it was only through such praise that her work would be allowed to be published. Wheatley thus developed an impeccable skill for subtext in understanding this legacy, and thus rose to the occasion brilliantly through the underlining messages that she imbibes within the lines of her poetry. This was perhaps the only way to preserve the truth that she faced and lived through in the 18th century, perhaps the only way to commune with future generations of what tortures she might have faced being trapped in this psychological prison that her time imposed upon her body and mind. So too is the case with Nelson in her conversations with children through her heroic crown sonnet; the implications that she makes in this work must be carefully planted and beautifully orchestrated to capture the minds of the young readers that will have read her poem. Karen Chandler, a literary critic, writes of Nelson’s delicate process:

Chandler points to the very heart of the originality behind Nelson’s work here; children’s literature is often employed to teach life lessons and paint the world in black and white in its regard to morality. Nelson, however, seeks to explore the emotional implications of Till’s fate and which allow children to develop their own understanding of the shades of gray that exist within the morality of the world. Wheatley, in her elusive verse, provides a similar take on the world that she lives in. Taking a look at her poem, “On Being Brought from Africa to America” it is clearly distinguishable from her other poetry as this piece is as direct as Wheatley gets to the subject of slavery and in its entirety she praises her experience for having brought her to Christianity. This piece also happens to be one of her shorter poems being only eight lines in length. The direct language of this poem is clear to read and understand, however, it is in Wheatley’s subtext and wordplay that she weaves layers into work which cover the many levels of understanding a woman in her position:

What we can initially draw from this piece is stated most profoundly in the third line, “That there’s a God that there’s a Saviour too.” Wheatley, here, differentiates between the Christian God and a ‘Saviour’ which plays along with the rules of Christianity (in that God is the savior). This line seems to imply at first glance that from being brought over to American, it was mercy that led her to God who is also the savior of her life. Though a closer reading on this line implies that this God that she was introduced to is indeed not the savior, instead the life of slavery that she is imprisoned is so great a wrong that it will ultimately lead to the coming of this savior. There is also another reading wherein Wheatley acknowledges and accepts the Christian God as her own and in a retort to the social context of slavery, she forces those who scorn African Christians to quell their hate towards what is also apart of “God’s creation.” This reading is more avidly detailed by Mary McAleer Balkun:

As valid as this interpretation of Wheatley’s poem is, it does not acknowledge the same reading of what becomes the more important line of the piece, that separates God and savior as two different entities. In this line Wheatley not only challenges the wrong that it is to scorn the African race because of the color of their skin but also the Christian religion itself as this ‘God’ is certainly not intent on changing the way that things are done in the United States. Wheatley instead challenges the scorners by using the teachings of their own religion against them but also challenges Christianity for allowing the establishment of slavery. Wheatley’s positioning and italicized inclusion of the words ‘Pagan’ and ‘Saviour’ (Balkun makes mention that this may be a decision by the publisher rather than Wheatley, however, their position relative to each other in their line placement also connects them and makes them more relevant when the poem is heard) are terms taken from the Christian social circle to represent her own ideas. ‘Pagan’ here standing in as any religion that doesn’t adhere to Christian tradition and ‘Saviour’ meaning the Christian God or Jesus Christ in the Christian teachings, though in their form Wheatley skews them to represent as such: Pagan as in her African lands who’s religious beliefs coincided with nothing that the corrupt Christian Church has taught her and savior as in the individual who would eventually deliver the United States from its bonds of slavery. Perhaps to go even further, Wheatley’s making reference to herself in this line as she is the resultant of an obscure and rare set of circumstance which gives her a voice for the African population in the United States. Ultimately Wheatley juxtaposes a hidden voice to her piece whose message is stark in contrast to the religious idiom that can be read at face value in this poem. Even with its layers this sort of write is extremely risky for Wheatley and is expressed as such seemingly in the length of the piece which one might expect to be much longer being that it is on a very personal and important topic regarding her life’s story. It is in these dangerous subtleties that Wheatley excels over many of the literary figures of her era who didn’t have to face the constrictions that she did. It is also from this same struggle and talent that Wheatley fostered; that she becomes a pinnacle of a figure from which many literary generations thereafter have borrowed from. Particularly evident in all of Wheatley’s work, regardless of the interpretation, is the emotion that Wheatley is able to evoke from her audience—this natural talent lends itself to any message that the reader can take from her poetry; thus, the imprisoned Wheatley is honestly felt even through her poetry that might suggest another sentiment from a gloss-over reading of her work. Astrid Franke also notices this inherent quality in Wheatley’s work when reading her poem “To Maecenas” and summarizes it as a general synopsis of a poet’s life; “The close relationship poets enjoy across time and space is centered in a sympathetic reading. Empathy is possible because human feeling remain constant throughout history, though their expression varies.” (Melancholy Muse, Franke) Because of Wheatley’s roots as a neoclassicist and her ability to invoke the raw emotions into her poetry, it is more than likely possible to associate the progression of specifically the Romantic period. The Romantic movement, obviously being primarily a European literary movement would not have solely been fueled by the limited works of Wheatley alone, however, it is more important the sentiment that Wheatley’s poetry is an embodiment of, from which they might have drawn. Especially seeing that Wheatley as a female slave poet was making an enormous amount of noise in the Americas since having been interviewed by scholarly gentlemen in Boston to authenticate her poetry. In this aspect of sentiment in her poetry, Wheatley is largely aware and thus her enormous collection of elegies. Wheatley figured out at a very early point in her writing career that in using social, political and especially religious figures as the inspiration for her pieces she would not only tap into the masses at that given time in the 18th century but also be written into history along with them. The ensuing tension that Wheatley created in America regarding the topic of slavery was overwhelming when London got wind of the interview that had been conducted yet Wheatley was still a slave. The title of ‘genius in bondage’ was never given more truth than in this instance where although her brilliance was recognized in the United States and England, her captivity was still never challenged by the prominent men who so admired her work and the intellectuals in England were simply appalled by this, often mocking Boston on how they pride themselves for their civil liberties yet still do nothing to free Wheatley from slavery. Gay Gibson Cima informs us in his essay on, “Black and Unmarked: Phillis Wheatley, Mercy Otis Warren, and the Limits of Strategic Anonymity:”

Such is the heavy impact that Wheatley’s legend carried across the Atlantic, yet she herself could not speak up for the injustices that were wrought upon herself and her own race who were still largely traded as slaves throughout the world. As America became more disdainful of English culture and the rest of the world watched on, the English fought back with this card in hand specifically exploited by Wheatley’s genius. The English having always been the moral nation of the world took this opportunity into their ken and ran with it. Herein lies the influence that Wheatley had over social, political and literary senses in the 18th century world. It is in this genius that Wheatley is able to quietly influence beyond her physical borders as well as timely boundaries in literature. Her elegy soon became a thing of legend and she is remembered today as the master of this form. The elegy soon became the vehicle that moved Wheatley’s poetry from the academic world to the hungry masses as they craved to relate in instances such as the death of George Whitefield. Wheatley in her mastery of ventriloquism captured the hearts of all of Whitefield’s followers in his passing by delivering an elegy that invokes his voice from the dead. Her tactical interpretation of the woes of the United States in its current state was brilliantly orchestrated in her dramatization of Whitefield’s sermon from the dead. Wheatley’s elegy became so famed and sought after once her skills were honed and her intent was clear in her mind that she is by in far the sole heir to the neoclassical form from which only she has tampered with to such a degree. Franke again hailing compliments for Wheatley writes in his literary article, “Melancholy Muse”, “That, for Wheatley, an imagination tied to a melancholy mind may well compete with classical poetry, and in some instances be superior to it.” In Wheatley’s mastery of exploiting neoclassical verse for its ability to mask and disguise her voice beneath an array of indulging she had only alluded to even more restricted lifestyle that she had to carry out on a day to day basis. Upon looking over her letters, Wheatley seems even more glossed over in her everyday manner than she appears in her poetry. Perhaps as a default mechanism she resorted to this nature to appease her masters and only in deep contemplation when searching for the muse did she manage to veer a defiant head. In much of her letters there’s not an ounce of real Wheatley to be interpreted as she has fluffed her words so ardently and masked her poetess voice. There are, however, instances within letters to John Thornton wherein we get an insight as to what might have been going on in Wheatley’s mind. Wheatley writes to Thornton, “You propose my returning to Africa […] but why do you hon’d Sir, wish those poor men so much trouble as to carry me So long a voyage? Upon my arrival, how like a Barbarian Should I look to the Natives…” and a few lines later ends the letter with a reluctantly decision, “But be that as it will I resign it to God’s all wise governance; I think you heartily for your generous Offer—With sincerity—”. (158, Wheatley, Complete Writings) We get our first look into a Wheatley that shows an honest emotion in her reluctance to return to Africa for missionary work and there is much that can be inferred from this. Wheatley’s growth and enormous popularity in America would have instantly died away had she been carried off to Africa to spread Christianity to a people who do not even understand her language. Her poetry would have been constricted and soon fade into the pages of unwritten history had she been brought back to Africa. Wheatley obviously saw the plight in this plot and sought to ensure that she didn’t fade away easily. Her visible reluctance yet ultimate acquiescence to “God’s will” is a proof of her indirect defiance to accede to what most Americans who supported slavery might have wanted her to do. In another letter addressed to Rev. Samuel Hopkins, again Wheatley turns down the offer to travel to Africa on regards to missionary work, writing, “…I received at the same time a paper by which I understand there are two Negro men who are desirous of returning to their native Country, to preach the Gospel; But being much indispos’d by the return of my Asthmatic complaint, besides, the sickness of my mistress who has been long confin’d to her bed, & is not expected to live a great while; all these things render it impracticable for me to do anything at present with regard to that paper…” (151, Wheatley, Complete Writings) In these letters it is clear of Wheatley’s intent to stay in the United States to produce more work that would eventually influence the fate of a race. Wheatley’s style of writing and manipulating her audiences to into reading what they should want to read while also molding their own moral choices in regards to the matters of slavery and religion, had become so refined that it is revered as a hallmark of her work in any literary criticism that is written for her. Balkun is one such literary critic who supports the middle ground of interpretations that Wheatley is in fact genuine about her conversion and belief in Christianity, however she uses it to her own benefit so as to make her audience feel a sense of a guilt as a result of that allegiance to Christian laws. Balkun explains Wheatley’s fervor, “In effect, Wheatley's strategy casts the audience into the unfolding drama of the poem: She sets the stage, introduces the hypocritical stance that allows so-called Christians to accept and even promote slavery, and then lays the groundwork for a spiritual dilemma—either join with Wheatley, the black, female Christian in her critique of the existing power structure or accept the very position of “other” that she and all black Americans were expected to occupy.” (Balkun, Phillis Wheatley's Construction of Otherness and the Rhetoric of Performed Ideology) Balkun is right to see these underlying messages in Wheatley’s work however, she fails to take a step further and question the entirety of the possibility of some façade that Wheatley is presenting to her overseers in the world of print. To examine this façade further, I must take us back to Wheatley’s poem, “On Being Brought from Africa to America” wherein she writes, “Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain, / May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.” (13, Wheatley, Complete Writings) These two lines alone might reflect a message much more sinister than the flowery ode to Christianity that many literary critics like Balkun choose to accept as fact even in acknowledging the mysterious voice that underlines Wheatley’s work. The first line can be taken at face value, as it simply identifies the group of people that Wheatley intends to address in the next. Though the second line makes use of the word “refin’d” and also the phrase “angelic train” which if read closely enough, one can interpret “refin’d” as of relating to the Christian missionary promises of cleansing the African people and the “angelic train” would then be a reference to the Trans-Atlantic Slave trade which would resemble a train of ships across the Atlantic bringing Africans over to the Americas as well as sending missionaries over to Africa. In this reading the title of “On Being Brought from Africa to America” becomes more prevalent as it serves more so as a descriptor of the slave trade rather than a religious poem that should be read as a moral lesson for Christians in the United States. In my research on Wheatley’s poetry, and particularly my reading of other critical analyses of her work—I find it increasingly surprising that many critics take the leap to believe as much as to credit Wheatley for her masking her poetess voice within the boundaries of neoclassical style, and more specifically in this case in an eight line poem written in iambic pentameter, yet they still never attempt to go all the way with the idea that Wheatley might just have been smart enough to know her role in this 18th century society and as a genius poet, might also have had the common sense to use this role to her utmost advantage. The conversion process she bolstered in her letters and poems becomes important only before Wheatley’s message had been heard and as a poet trapped within the confines of the overbearingly religious social context, it’s only proper that Wheatley be credited for figuring out that all she had to do was play along with religion in order to be heard on an international and ultimately timeless stage. In Henry Louis Gate’s book, The Trials of Phillis Wheatley, he writes “…this helps us to understand why Wheatley’s examination was so important. If she had indeed written her poems, then this would demonstrate that Africans were human beings and should be liberated from slavery. If, on the other hand, she had not written, or could not write her poems, or if indeed she was like a parrot who speaks a few words plainly, then that would be another matter entirely. Essentially, she was auditioning for the humanity of the entire African people.” (26-27, Gates) Whether Wheatley’s intentions were for her own salvation or for the salvation of her entire race (which most likely entails salvation for herself as well) we may never know. Her ability to allow such limited insight into her psyche through her many writings as well as her correspondences with other notable figures of the time is a brilliance paralleled only by her ability to stage windows into her own mind through the subtlety of her poetry. It is in this that the Romantics learned their windows to the soul that allowed them to pour their hearts out onto the page in such scenic fashion. It is in Wheatley’s neoclassical mastery that she becomes to bridge between these two eras of literature, and it is in this bridge that she is able to encompass all that is the American Enlightenment. More impressively Wheatley died at the age of 31 having never even known the reaches of which her genius inspired. Even in the wake of all that Wheatley has accomplished in a time when women, no less slaves, were almost equaled with no rights in society; still she’s criticized for having abandoned her people or taken on the voice of white America. To this, my final assessment would advise any attuned and insightful reader to peer through the subtext of Wheatley’s verse, she has done all that she could have possibly done in the situation that was given to her, and as we are able to understand poetry in a more vivid light, so too does her work evolve with that understanding. ReferencesBalkun, M.M. “Phillis Wheatley’s construction of otherness and the rhetoric of performed ideology.” African American Review. Spring 2002 121-135. Boren, M.E. “A fiery furnace and a sugar train: Metaphors that challenge the legacy of Phillis Wheatley’s ‘On being brought from Africa to America’.” CEA Critic. Fall 2004 38-56. Cima, G.G. “Black and unmarked: Phillis Wheatley, Mercy Otis Warren, and the limits of strategic anonymity” Theatre Journal. December 2000 465-495. Franke, A. “Phillis Wheatley, melancholy muse.” New England Quarterly-A Historical Review of New England Life and Letters. June 2004 224-251. Gates, Henry Louis. The Trials of Phillis Wheatley : America’s first Black poet and her encounters with the founding fathers. New York, Basic Civitas Books, 2003. Wheatley, Phillis. Phillis Wheatley: Complete Writings. Penguin Books, 2001. Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in Literature |