|

From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 9 NO. 1 Norm or Necessity? The Non-Interference Principle in ASEAN

By Tram-Anh Nguyen

Cornell International Affairs Review

2016, Vol. 9 No. 1 | pg. 2/2 | «

To understand why ASEAN insisted on keeping the non-interference principle in its 2007 Charter, even though the norm itself does not determine ASEAN's pattern of interference, one must understand the value of this principle to ASEAN member states. Realist scholars like Haacke and Jones have incorrectly assumed that all ASEAN member states value the non-interference principle for protecting their sovereignty. However, the ten ASEAN countries have very different political systems, interests and priorities, and thus different valuations of this principle. Therefore, they have different levels of resistance toward changes to the non-interference norm. An examination of ASEAN members' diverse reactions toward challenges to the non-interference principle illuminates their attitudes.

How much an ASEAN country resists changing the non-interference principle depends on how confident it is of its immunity to future ASEAN interference in the absence of the non-interference principle. I argue that this confidence (called "Confidence" hereafter) depends on two factors: the country's level of democratization and its relative power in the region. The more democratic a state is, the more legitimacy the government has and the less it worries that ASEAN would come under international pressure to interfere in its domestic affairs on the grounds of supporting human rights or democracy. On the other hand, the more relative power an ASEAN country has, the less other member states wish to offend this country and damage their relations with it.

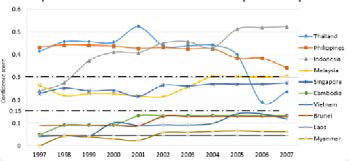

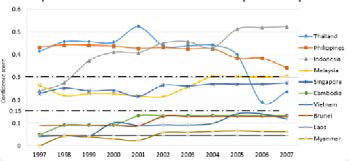

To illustrate this point, I create a Confidence scale from 0 to 1 to measure ASEAN members' confidence that their sovereignty will not come under threat even without the non-interference principle. Each country's score is the weighted sum of its level of democratization (calculated from its Freedom House scoreiv) and its relative power (a composite indicator estimated based on its GDP, population and military expenditures).v Graph 1 shows the Confidence scores of all ASEAN countries in the period 1997-2007.

Based on these scores, ASEAN members can be divided into three groups. The first group with Confidence score less than 0.15 includes weaker and less democratic members of ASEAN, such as Myanmar, Laos, Brunei, and Vietnam. I predict that these countries would most resist any change to the non-interference norm, because they would be the most likely targets of future ASEAN intervention, given the undemocratic nature of their regimes and their limited relative power. The members of the second group, with Confidence scores ranging from 0.15 to 0.3, are Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia (before 1999) and Thailand (after 2005). These countries are major powers in ASEAN, but with relatively democratic regimes. Thus, they still want to keep the non-interference principle to protect their illiberal political system, but they are more flexible regarding its applications due to their confidence in their relative power. The last group with the highest Confidence score (above 0.3) includes all democratic countries in ASEAN: the Philippines, Indonesia (after 1999), and Thailand (before 2005). They are the most confident in their legitimacy because of their more democratic systems. Therefore, I predict they would be the strongest advocates for changes to the noninterference principle in ASEAN.

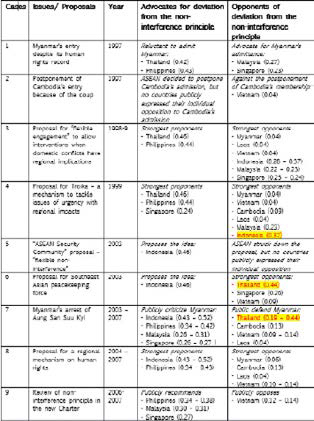

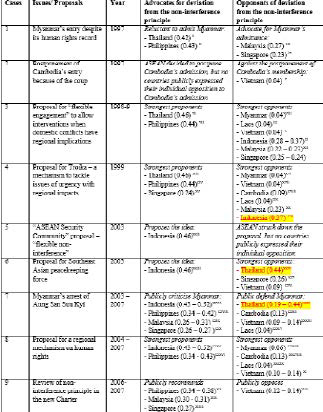

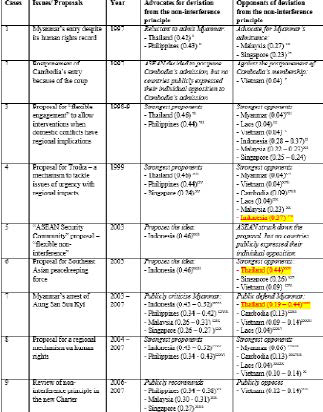

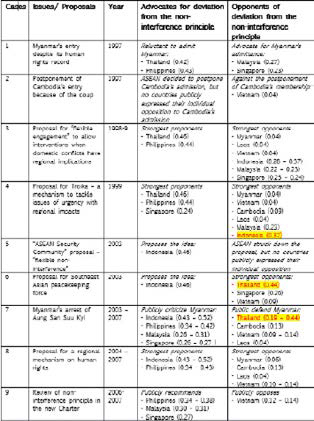

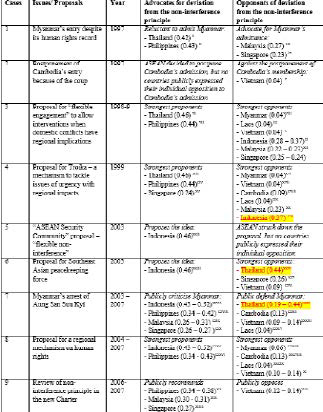

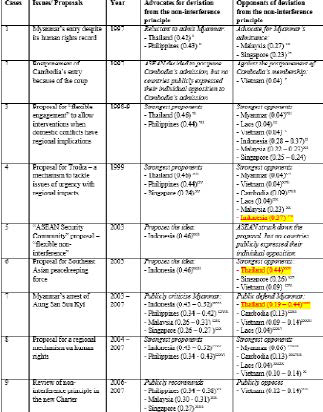

To test my hypotheses, I examine the diverse responses of ASEAN members to proposals and issues that challenged the noninterference principle between 1997 and 2007. Because ASEAN exercises quiet diplomacy and holds private meetings, these responses can only be collected from foreign ministers' public statements and interviews with journalists. Therefore, one can only observe the reactions of countries with the strongest opinions regarding whether ASEAN should adhere or deviate from the non-interference principle. Table 2 (Challenges for the noninterference principle in ASEAN 1997-2007) represents cases when there were diverse opinions regarding the application of the non-interference principle, together with the strongest proponents and opponents of changes to the principle. Their Confidence scores are put in parentheses next to their names. For issues that lasted more than one year, the ranges of Confidence scores are reported instead of a single score.

The results in Table 2 fit my hypothesized expectations for the three groups, except for the highlighted cases of Indonesia and Thailand (which will be addressed in further detail later). Countries in Group 1 (with a Confidence score less than 0.15) persistently opposed any deviations from the noninterference principle. For them, the noninterference principle guarantees protection for their weaker and less democratic regimes. They are afraid that any small deviation from the principle will set a dangerous precedent for future ASEAN interference in domestic affairs.

Apart from the highlighted cases of Indonesia and Thailand, countries in Group 3 (with a Confidence score more than 0.3), with high Freedom House score and strong relative power, are the strongest proponents for changes to the non-interference principle. As these countries are democratic, their governments have to respond to their constituents and bear responsibility for the results of their foreign policies. Therefore, when international criticism of the non-interference principle started to damage ASEAN's reputation, it also lowered these states' credibility and damaged relations with their major partners (the US, the EU, and Japan).

Therefore, these democratic governments felt the need to change the non-interference principle and improve their images. Moreover, democratic countries often have strong civil society actors who oppose human rights abuses by their undemocratic ASEAN partners and demand actions from their democratic governments. For example, in 2004, the Philippines' parliamentarians pressured the government to oppose Myanmar becoming the chair of ASEAN in 2006 because of its continued detention of pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi.48 This also explains why all the proposals to change the interpretation of the non-interference principle came from democratic ASEAN members.

Table 1: Challenges for the Non-Interference Principle in ASEAN

Countries in Group 2 (with a Confidence score more than 0.15 but less than 0.3) have the most inconsistent patterns of adherence to the non-interference principle. The countries in this group, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia (before 1999) and Thailand (after 2005), are concerned enough for their illiberal governments to want to maintain the existence of the non-interference principle. However, they are also confident enough in their relative power within ASEAN to deviate from the non-interference principle when the cost of upholding it exceeds its benefits.

For instance, in 1998, Singapore strongly opposed Thailand's proposal for "flexible engagement" to loosen the principle of non-interference (case 3). However, in 1999, Singapore advocated for the Troika mechanism to respond to urgent internal issues that may have spillover effects in the region (case 4). Singapore's position was affected by its concern about the regional economic recovery and investors' confidence. Singapore's former Foreign Minister, S. Jayakumar, emphasized that "ASEAN faced a crisis of confidence."49 The international community had criticized ASEAN's non-interference principle for paralyzing the organization during the 1997 Asian Financial crisis.

Graph 1: Confidence Scores of ASEAN countries (1997-2007)

Singapore realized that unless ASEAN made some changes to the non-interference norm, its economy would suffer. Nevertheless, it still wished to maintain the non-interference principle to protect its own undemocratic government. Although the Troika mechanism was clearly a deviation from the non-interference principle, Jayakumar tried to argue that it should not be construed as "compromising sovereignty," but as "greater cooperation and pooling of our resources to deal with problems that countries cannot handle on their own separately but yet can affect the others."50

Activists gather to protest the detention of Aung San Suu Kyi.

Indonesia and Thailand provide the three observed instances of prediction outliers, suggesting the analytical limits of the Confidence score. When Indonesia's Confidence score was 0.37, it still opposed the proposal for Troika in 1999. Indonesia's confidence score increased dramatically from 0.27 in 1998 to 0.37 in 1999 because Indonesia's nondemocratic President Suharto was forced to step down because of his failure to fix the problems of the financial crisis.

Indonesia's Freedom House score changed immediately from 5 to 3.5. Although Suharto's successor, President B. J. Habibie, started to democratize the country in 1999, its transition into a full democracy was not complete until 2003. In the four years after Suharto stepped down, two presidents were ousted by the Indonesian parliament.51 With its unstable new democracy, Indonesia in 1999 was not yet ready for changes to ASEAN's non-interference principle. The Confidence score, which is strongly based on the Freedom House score, cannot pick up Indonesia's vulnerability during this transition from 1998 to 2003. Starting from 2003, Indonesia's behavior fits this paper's prediction well. It tirelessly advocated for a reinterpretation of the non-interference principle with proposals for ASEAN Security Community (case 5), a Southeast Asian peacekeeping force (case 6), and an ASEAN human rights mechanism (case 8).

Thailand's behavior in 2003 and 2004 also deviates from the prediction based on the Confidence score. This result is also due to the insensitivity of the Freedom House scores. Although Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra was democratically elected in 2001, he was not a liberal leader. Under his harsh policies, Thailand's human rights record worsened. His 2003 police crackdown on drug-trafficking caused the deaths of an estimated 2,200 suspects.52 His suppression of Muslim separatists in southern Thailand led to the infamous Tak Bai incident in 2004, when 87 protestors died of suffocation after they were packed into military trucks.53 Thaksin kept using the non-interference principle to prevent discussions of these incidents in ASEAN. He threatened to walk out of the ASEAN Summit in 2004 if anyone mentioned the Tak Bai incident.54 Therefore, even though technically Thailand was still a democratic country in 2003 and 2004 (and thus its Freedom House score was still 2.5), its government started to need the protection of the non-interference principle to shield its human rights abuses from criticism.

The more democratic a country is, and the more relative power it has within ASEAN, the less it needs the non-interference norm.

By examining individual ASEAN members' attitude toward the non-interference norm, one can clearly see that the strongest supporters of ASEAN's strict adherence to the non-interference principle are weaker, less democratic countries. The more democratic a country is, and the more relative power it has within ASEAN, the less it needs the non-interference norm. However, because relative power is relative – that is, an increase in country A's power causes a decrease in that of other countries – it is not possible to mitigate its influence on a country's stance regarding the non-interference principle. Only democratization is likely to prompt ASEAN to change this principle. Indonesia, for instance, transformed from a staunch protector of the non-interference principle into the most active advocate for its modification after its own democratization. Thus, as long as there are still few democratic countries in ASEAN, the non-interference norm is still likely to remain.

This paper has evaluated the importance of the non-interference principle in ASEAN and has explained its members' steadfast loyalty to it by examining the organization's actions from 1997 to 2007. Analyzing cases of violation and non-violation of the noninterference principle, it provides strong evidence that the non-interference principle has not determined whether ASEAN interferes in a domestic conflict or not. To explain ASEAN's attachment to the non-interference principle, I created a novel Confidence (of immunity) index and examined individual ASEAN members' responses to proposed challenges to the principle during this decade. The results demonstrate that the greater a state's level of democratization and relative power, the more confident it is of its immunity to future ASEAN interference and thus the less it insists on the continued existence of the non-interference principle in ASEAN. However, as relative power is relative, the main reason why ASEAN still retains the non-interference principle is because its democratic members are a minority. ASEAN's non-democratic members need the principle to give them confidence in their immunity to external intervention. Therefore, a logic of consequences best accounts for ASEAN's behavior regarding the non-interference principle.

Abbugao, Martin. "ASEAN Charter Aims to Protect Human Rights, Uphold Democracy: Draft." Agence France-Presse 9 Nov. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Acharya, Amitav. Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and the Problem of Regional Order. Routledge, 2009. Print.

AFP. "Myanmar Says Will Accept ASEAN Envoy's Visit." Agence France-Presse 12 Dec. 2005. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Nine Killed as Myanmar Junta Cracks down on Protests." Agence France-Presse 27 Sept. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Thai PM Warns of ASEAN Walkout If Row Starts over Muslim Protester Deaths." Agence France-Presse 25 Nov. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Alford, Peter. "Neighbours Fear Burma." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 10 July 1998: 007. Print.

"Thais Push Radical Shift in ASEAN." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 6 July 1998: 006. Print.

ASEAN. "ASEAN." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

BBC. "ASEAN Chief Doubts Influence of Malaysian Ultimatum on Burma." BBC Monitoring International Reports 31 Mar. 2005. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"ASEAN Foreign Ministers Differ on Embracing Globalization Trend." BBC Monitoring International Reports 25 July 2000. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Indonesia Opposes Changing ASEAN's Nonintervention Policy." BBC Monitoring International Reports 15 July 1998. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Vietnamese, Burmese Leaders Discuss ASEAN, Regional, Bilateral Issues." BBC Monitoring International Reports 11 Aug. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Vietnam Offers Refuge to Foreigners Fleeing Cambodia." BBC Monitoring International Reports 12 July 1997. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Bernama. "Vietnam Benefit from ASEAN's Non-Interference Stance." Bernama: The Malaysian National News Agency (Malaysia) 27 Jan. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Burton, John. "Leadership Change in Burma Tests Asean's Relations with US and EU." Financial Times 21 Oct. 2004. Financial Times. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Malaysia Heads Calls for Burma to Be Barred from Taking over." Financial Times (London, England) 28 Mar. 2005: 06. Print.

Caballero-Anthony, Mely. "Partnership for Peace in Asia: ASEAN, the ARF, and the United Nations." Contemporary Southeast Asia 24.3 (2002): 528–548. Print.

Caballero-Anthony, Mely, and Amitav Acharya. "UN Peace Operations and Asian Security." UN Peace Operations and Asian Security. Routledge, 2005. Print.

Chong, Florence. "Trouble-Shooters Look out for the next Big Disaster." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 26 July 2000: 031. Print.

Cotton, James. "Against the Grain: The East Timor Intervention." Survival 43.1 (2001): 127–142. Print.

"The Emergence of an Independent East Timor: National and Regional Challenges." Contemporary Southeast Asia (2000): 1–22. Print.

"Data | The World Bank." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Doyle, Michael W., and Nicholas Sambanis. Making War and Building Peace United Nations Peace Operations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006. Print.

DPA. "ASEAN to Reiterate Call for Myanmar to Increase ‘Democratic Space.'" Deutsche Press-Agentur 25 Oct. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Bold Moves Proposed to Prevent ASEAN from Atrophy." Deutsche Press-Agentur 6 Jan. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Indonesian President Slams Unilateralism, Promotes Dialogue." Deutsche Press-Agentur 30 June 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Singapore Concerned over Myanmar's National Reconciliation Process." Deutsche Press-Agentur 22 Oct. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Dupont, Alan. "ASEAN's Response to the East Timor Crisis." (2000): n. pag. Google Scholar. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Freedom House." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Funston, John. "ASEAN: Out of Its Depth?" Contemporary Southeast Asia (1998): 22–37. Print.

García, María del Mar Hidalgo. "The Ethnic Conflicts in Myanmar: Kachin." Geopolitical Overview of Conflicts 2013. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, 2013. 341–368. Google Scholar. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Garran, Robert. "Ministers Put Good Neighbours before Good Sense." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 28 July 1998: 013. Print.

Haacke, Jürgen. "ASEAN's Diplomatic and Security Culture: A Constructivist Assessment." International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 3.1 (2003): 57–87. Print.

Helmke, Belinda. "The Absence of ASEAN: Peacekeeping in Southeast Asia." Pacific News 31 (2009): 4–6. Print.

"IMF DataMapper." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Indonesia | Freedom House." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Iran News. "Southeast Asia Lays Path for Future." Iran News (Iran) 14 Jan. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Joint Communique of the 30th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting." Subang Jaya, Malaysia: N.p., 1997. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Joint Communique of the 39th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting." Kuala Lumpur: N.p., 2006. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Jones, Lee. "ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: From Cold War to Conditionality." The Pacific Review 20.4 (2007): 523–550. Print.

"ASEAN's Unchanged Melody? The Theory and Practice of ‘non-Interference'in Southeast Asia." The Pacific Review 23.4 (2010): 479–502. Print.

Kazmin, Amy. "Singapore Warns of North Asian Economic Threat: Asean Urged to Speed up Financial Reforms or Face Becoming ‘Irrelevant.'" Financial Times (London, England) 25 July 2000: 1. Print.

"Suu Kyi Arrest Threatens Asean Credibility: Burma Will Present Plans for Democracy at This Week's Bali Summit. They Are Unlikely to Win over Sceptics. Amy Kazmin Reports." Financial Times (London, England) 6 Oct. 2003: 2. Print.

Khoo, Nicholas. "Deconstructing the ASEAN Security Community: A Review Essay." International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 4.1 (2004): 35–46. Print.

Krasner, Stephen D. Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy. Princeton University Press, 1999. Print.

Kyodo News International. "ASEAN Official Complete Drafting of Landmark Charter." Kyodo News International, Inc. 22 Oct. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Lee, Kim Chew. "ASEAN Urges Myanmar to Accept Role of the UN." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 17 June 2003. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Peacekeeper Plan for Region Shelved Jakarta's Proposal Fails to Get Support from Its Partners in Asean Which Say It Is Too Costly and Premature." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 29 June 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Potential for Action Shows There's Life in Asean yet." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 24 July 2000: 30. Print.

Levy, Marc A., and Marc A. Levy. "European Acid Rain: The Power of Tote-Board Diplomacy." Institutions for the Earth: Sources of Effective International Environmental Protection. Ed. Peter M. Haas and Robert O. Keohane. MIT Press, 1993. Print.

Manila Standard Today. "Asean Dared to Act on Myanmar." Manila Standard Today (Philippines) 7 Apr. 2005. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Mansor, Lokman. "PM: We Support Sanctions against Errant Members." New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia) 14 Jan. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Manthorpe, Jonathan. "Economic Club Opens Arms for Mynamar." Hamilton Spectator, The (Ontario, Canada) 7 Dec. 1996: D12. Print.

"NewsBank InfoWeb." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Parameswaran, P. "ASEAN Voices ‘Revulsion' over Myanmar Crackdown." Agence

France-Presse 27 Sept. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Peachey, Paul. "Thailand Faces Tough Questions but Likely to Escape Censure at ASEAN Summit." Agence France-Presse 23 Nov. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Peou, Sorpong. "The Subsidiarity Model of Global Governance in the UN-ASEAN Context." Global governance 4 (1998): 439. Print.

Purba, Kornelius. "Building ‘Non-Interference.'" WorldSources Online 15 Oct. 2003. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Ramcharan, Robin. "ASEAN and Non-Interference: A Principle Maintained." Contemporary Southeast Asia (2000): 60–88. Print.

Saengchan, Nattapol. "Undesirable Consequences of an ASEAN Peacekeeping Force." Jakarta Post 2 Mar. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Severino, Rodolfo C. "Sovereignty, Intervention and the ASEAN Way." ASEAN Scholars' Roundtable. Singapore. 2000.

Siangkin. "Is There a Lack of Focus in Indonesia's Foreign Policy?" Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 2 Oct. 2000: 44. Print.

"Manila to Invoke Principle of Non-Intervention." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 21 July 2000: 38. Print.

Singapore, Amy Kazmin in. "Asean Charter Falls Foul of Burma Divisions." Financial Times (London, England) 21 Nov. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Singer, J. David. "Reconstructing the Correlates of War Dataset on Material Capabilities of States, 1816–1985." International Interactions 14.2 (1988): 115–132. Print.

Singer, J. David, Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey. "Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 18201965." Peace, war, and numbers 19 (1972): n. pag. Google Scholar. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Stewart, Ian. "ASEAN Divides over Intervention Plan." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 20 July 1998: 007. Print.

"Thailand | Freedom House." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

The Straits Times. "Asean's Peace." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 8 Mar. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Thailand to Push for ‘Troika' Plan to Act in Crises." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 19 July 2000: 30. Print.

The Washington Times. "Telling It like It Is to ASEAN." Washington Times, The (DC) 4 Aug. 1997: A18. Print.

Timberlake, Ian. "Southeast Asia Takes ‘Breakthrough' Step toward Regional Rights Body." Agence France-Presse 25 July 2005. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Torode, Greg. "Crisis-Hit Nations to ‘Usher in' New Order." South China Morning Post (Hong Kong) 4 July 1998: 11. Print.

"UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset." N.p., 2014. Web. 13 Jan. 2015. Wheeler, Nicholas J., and Tim Ddunne. "East Timor and the New Humanitarian Interventionism." International Affairs 77.4 (2001): 805–827. Print.

- Jonathan Manthorpe, “Economic Club Opens Arms for Mynamar,” Hamilton Spectator, The (Ontario, Canada), December 7, 1996, FINAL edition.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Vietnam Offers Refuge to Foreigners Fleeing Cambodia - Japanese Report,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, July 12, 1997, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0F99F5D92E430FE4?p=AWNB.

- Peter Alford, “Thais Push Radical Shift in ASEAN,” Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia), July 6, 1998, 1 edition.

- Peter Alford, “Neighbours Fear Burma,” Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia), July 10, 1998, 1 edition.

- Greg Torode, “Crisis-Hit Nations to ‘Usher in’ New Order,” South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), July 4, 1998, 2 edition.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Indonesia Opposes Changing ASEAN’s Nonintervention Policy,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, July 15, 1998, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0F98E44997028BED?p=AWNB.

- Ian Stewart, “ASEAN Divides over Intervention Plan,” Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia), July 20, 1998, 1 edition.

- “Thailand to Push for ‘Troika’ Plan to Act in Crises,” Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), July 19, 2000.

- “ASEAN Foreign Ministers Differ on Embracing Globalization Trend,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, July 25, 2000, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0F97DCB197842F3A?p=AWNB.

- Ibid.

- Kim Chew Lee, “Potential for Action Shows There’s Life in Asean yet,” Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), July 24, 2000.

- Amy Kazmin, “Singapore Warns of North Asian Economic Threat: Asean Urged to Speed up Financial Reforms or Face Becoming ‘Irrelevant,’” Financial Times (London, England), July 25, 2000, USA Ed2 edition.

- Lee, “Potential for Action Shows There’s Life in Asean yet.”

- Ibid.

- “ASEAN Foreign Ministers Differ on Embracing Globalization Trend.”

- Siangkin, “Is There a Lack of Focus in Indonesia’s Foreign Policy?,” Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), October 2, 2000.

- Kornelius Purba, “Building ‘Non-Interference,’” WorldSources Online, October 15, 2003, http://infoweb.newsbank. com/resources/doc/nb/news/0FE3C061A81B689A?p=AWNB.

- Kim Chew Lee, “Peacekeeper Plan for Region Shelved - Jakarta’s Proposal Fails to Get Support from Its Partners in Asean Which Say It Is Too Costly and Premature,” Straits Times,

- The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), June 29, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/10382BB397AEEDE8?p=AWNB.

- “Undesirable Consequences of an ASEAN Peacekeeping Force,” WorldSources Online, March 2, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/101170A261AEB861?p=AWNB.

- “Asean’s Peace,” Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), March 8, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/1012EE02450C0526?p=AWNB.

- Ibid.

- “Indonesian President Slams Unilateralism, Promotes Dialogue,” Deutsche Press-Agentur, June 30, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/1038A7DA897A2B9E?p=AWNB.

- “ASEAN to Reiterate Call for Myanmar to Increase ‘Democratic Space,’” Deutsche Press-Agentur, October 25, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/106D64150A9254A8?p=AWNB.

- “ROUNDUP: Singapore Concerned over Myanmar’s National Reconciliation Process,” Deutsche Press-Agentur, October 22, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/105E37BFA309C164?p=AWNB.

- “Malaysia Heads Calls for Burma to Be Barred from Taking over,” Financial Times (London, England), March 28, 2005, London Ed1 edition.

- “ASEAN Chief Doubts Influence of Malaysian Ultimatum on Burma,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, March 31, 2005, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/10934EBC704090A0?p=AWNB.

- Ibid.

- “Vietnamese, Burmese Leaders Discuss ASEAN, Regional, Bilateral Issues,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, August 11, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/1046D6F5B164ADEF?p=AWNB.

- “ASEAN Chief Doubts Influence of Malaysian Ultimatum on Burma.”

- Ian Timberlake, “Southeast Asia Takes ‘Breakthrough’ Step toward Regional Rights Body,” Agence France-Presse, July 25, 2005, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/10B982B862EE0058?p=AWNB.

- “Southeast Asia Lays Path for Future,” Iran News (Iran), January 14, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/ doc/nb/news/11C7824E0599DA68?p=AWNB.

- “ASEAN Official Complete Drafting of Landmark Charter,” Kyodo News International, Inc., October 22, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/11C774790F713388?p=AWNB.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Amy Kazmin in Singapore, “Asean Charter Falls Foul of Burma Divisions,” Financial Times (London, England), November 21, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/11D19704A8424E10?p=AWNB.

- Lokman Mansor, “PM: We Support Sanctions against Errant Members,” New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), January 14, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/116B094433728070?p=AWNB.

- “Bold Moves Proposed to Prevent ASEAN from Atrophy,” Deutsche Press-Agentur, January 6, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/11683673268757A0?p=AWNB.

- “Vietnam Benefit from ASEAN’s Non-Interference Stance,” Bernama: The Malaysian National News Agency (Malaysia), January 27, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/1182C0733A457EE8?p=AWNB.

- The ten countries are Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam.

- Conflict may have started or ended outside of this time frame

- This conflict is included because East Timor was Indonesia’s colony and ASEAN referred to this conflict as an internal issue for Indonesia (Dupont 163).

- Freedom House measures states’ political rights and civil liberties on a scale from 1 (most democratic) to 7 (least democratic).

- More details on the calculation method are given in Appendix A.

- More details on sources for Table 2 are listed in Appendix B.

- Data sources: GDP -“IMF DataMapper.”; Population - “Data | The World Bank,” accessed January 13, 2015, http://data.worldbank.org/; Military expenditures - J. David Singer, Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey, “Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 1820-1965,” Peace, War, and Numbers 19 (1972), http://www.correlatesofwar.org/COW2%20Data/Capabilities/nmc4.htm; J. David Singer, “Reconstructing the Correlates of War Dataset on Material Capabilities of States, 1816–1985,” International Interactions 14, no. 2 (1988): 115–32.

The Confidence scale measures ASEAN members' confidence that their sovereignty will not be subject to external interference. The first component of the index, democracy, is based on the Freedom House score of each country. Freedom House measures political rights and civil liberties of states, giving each country a score from 1 (most democratic) to 7 (least democratic). Here, this score is rescaled to fit the 0 to 1 scale and to vary in the same direction with the confidence level. For example, if a country's Freedom House score is 4 (like Indonesia in 1999), its Democracy index is calculated according to the formula below: Dem=(7-4)/(7-1)=3/6=0.5

The second component of the Confidence scale, relative power (RP), is estimated from three proxies: GDP, population and military expenditures.7 I calculate the GDP index (GDP) by dividing a country's GDP by ASEAN's total GDP of that same year. For example, in 2006, Thailand's GDP was 207.089 billion USD, while the total GDP of ASEAN was 1109.629 billion USD. Thus, its GDP index equals to 207.089/1109.629=0.187. The population index (Pop) and the military expenditures index (Milex) for each country are calculated using the same method with the GDP index. Because there has not been any dominant theory on which factor is more important to a country's relative power than the others, we distribute the weight equally for all factors. So the RP index is calculated using the formula:

RP=1/3×GDP+1/3×Pop+1/3×Milex

The Confidence scale of each country, which measures the country's confidence in its immunity against future ASEAN's intervention in the absence of the non-interference principle, is the weighted sum of the two components – democracy (Dem) and relative power (RP):

Confidence=1/2×Dem+1/2×RP

0≤Confidence≤1

Table 2, showing cases when there were diverse opinions regarding the application of the non-interference principle from 1997 to 2007, is reproduced below with detailed sources for ASEAN members' positions in each case:

Image Attributions

By Gunawan Kartapranata (Own work) ASEAN Nations Flags in Jakarta 3.jpg 2011[CC-BY-SA-3.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ASEAN_Nations_Flags_in_Jakarta_3.jpg)], via Wikimedia Commons.

By Francois Polito (Own work) Manifestion pour la liberation de aung san suu kyi au siege de l ONU a new york.jpg 2003 [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Manifestion_pour_la_liberation_de_aung_san_suu_ kyi_au_siege_de_l_ONU_a_new_york.jpg)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Abbugao, Martin. "ASEAN Charter Aims to Protect Human Rights, Uphold Democracy: Draft." Agence France-Presse 9 Nov. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Acharya, Amitav. Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and the Problem of Regional Order. Routledge, 2009. Print.

AFP. "Myanmar Says Will Accept ASEAN Envoy's Visit." Agence France-Presse 12 Dec. 2005. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Nine Killed as Myanmar Junta Cracks down on Protests." Agence France-Presse 27 Sept. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Thai PM Warns of ASEAN Walkout If Row Starts over Muslim Protester Deaths." Agence France-Presse 25 Nov. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Alford, Peter. "Neighbours Fear Burma." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 10 July 1998: 007. Print.

"Thais Push Radical Shift in ASEAN." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 6 July 1998: 006. Print.

ASEAN. "ASEAN." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

BBC. "ASEAN Chief Doubts Influence of Malaysian Ultimatum on Burma." BBC Monitoring International Reports 31 Mar. 2005. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"ASEAN Foreign Ministers Differ on Embracing Globalization Trend." BBC Monitoring International Reports 25 July 2000. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Indonesia Opposes Changing ASEAN's Nonintervention Policy." BBC Monitoring International Reports 15 July 1998. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Vietnamese, Burmese Leaders Discuss ASEAN, Regional, Bilateral Issues." BBC Monitoring International Reports 11 Aug. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Vietnam Offers Refuge to Foreigners Fleeing Cambodia." BBC Monitoring International Reports 12 July 1997. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Bernama. "Vietnam Benefit from ASEAN's Non-Interference Stance." Bernama: The Malaysian National News Agency (Malaysia) 27 Jan. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Burton, John. "Leadership Change in Burma Tests Asean's Relations with US and EU." Financial Times 21 Oct. 2004. Financial Times. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Malaysia Heads Calls for Burma to Be Barred from Taking over." Financial Times (London, England) 28 Mar. 2005: 06. Print.

Caballero-Anthony, Mely. "Partnership for Peace in Asia: ASEAN, the ARF, and the United Nations." Contemporary Southeast Asia 24.3 (2002): 528–548. Print.

Caballero-Anthony, Mely, and Amitav Acharya. "UN Peace Operations and Asian Security." UN Peace Operations and Asian Security. Routledge, 2005. Print.

Chong, Florence. "Trouble-Shooters Look out for the next Big Disaster." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 26 July 2000: 031. Print.

Cotton, James. "Against the Grain: The East Timor Intervention." Survival 43.1 (2001): 127–142. Print.

"The Emergence of an Independent East Timor: National and Regional Challenges." Contemporary Southeast Asia (2000): 1–22. Print.

"Data | The World Bank." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Doyle, Michael W., and Nicholas Sambanis. Making War and Building Peace United Nations Peace Operations. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006. Print.

DPA. "ASEAN to Reiterate Call for Myanmar to Increase ‘Democratic Space.'" Deutsche Press-Agentur 25 Oct. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Bold Moves Proposed to Prevent ASEAN from Atrophy." Deutsche Press-Agentur 6 Jan. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Indonesian President Slams Unilateralism, Promotes Dialogue." Deutsche Press-Agentur 30 June 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Singapore Concerned over Myanmar's National Reconciliation Process." Deutsche Press-Agentur 22 Oct. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Dupont, Alan. "ASEAN's Response to the East Timor Crisis." (2000): n. pag. Google Scholar. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Freedom House." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Funston, John. "ASEAN: Out of Its Depth?" Contemporary Southeast Asia (1998): 22–37. Print.

García, María del Mar Hidalgo. "The Ethnic Conflicts in Myanmar: Kachin." Geopolitical Overview of Conflicts 2013. Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, 2013. 341–368. Google Scholar. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Garran, Robert. "Ministers Put Good Neighbours before Good Sense." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 28 July 1998: 013. Print.

Haacke, Jürgen. "ASEAN's Diplomatic and Security Culture: A Constructivist Assessment." International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 3.1 (2003): 57–87. Print.

Helmke, Belinda. "The Absence of ASEAN: Peacekeeping in Southeast Asia." Pacific News 31 (2009): 4–6. Print.

"IMF DataMapper." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Indonesia | Freedom House." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Iran News. "Southeast Asia Lays Path for Future." Iran News (Iran) 14 Jan. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Joint Communique of the 30th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting." Subang Jaya, Malaysia: N.p., 1997. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Joint Communique of the 39th ASEAN Ministerial Meeting." Kuala Lumpur: N.p., 2006. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Jones, Lee. "ASEAN Intervention in Cambodia: From Cold War to Conditionality." The Pacific Review 20.4 (2007): 523–550. Print.

"ASEAN's Unchanged Melody? The Theory and Practice of ‘non-Interference'in Southeast Asia." The Pacific Review 23.4 (2010): 479–502. Print.

Kazmin, Amy. "Singapore Warns of North Asian Economic Threat: Asean Urged to Speed up Financial Reforms or Face Becoming ‘Irrelevant.'" Financial Times (London, England) 25 July 2000: 1. Print.

"Suu Kyi Arrest Threatens Asean Credibility: Burma Will Present Plans for Democracy at This Week's Bali Summit. They Are Unlikely to Win over Sceptics. Amy Kazmin Reports." Financial Times (London, England) 6 Oct. 2003: 2. Print.

Khoo, Nicholas. "Deconstructing the ASEAN Security Community: A Review Essay." International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 4.1 (2004): 35–46. Print.

Krasner, Stephen D. Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy. Princeton University Press, 1999. Print.

Kyodo News International. "ASEAN Official Complete Drafting of Landmark Charter." Kyodo News International, Inc. 22 Oct. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Lee, Kim Chew. "ASEAN Urges Myanmar to Accept Role of the UN." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 17 June 2003. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Peacekeeper Plan for Region Shelved Jakarta's Proposal Fails to Get Support from Its Partners in Asean Which Say It Is Too Costly and Premature." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 29 June 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Potential for Action Shows There's Life in Asean yet." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 24 July 2000: 30. Print.

Levy, Marc A., and Marc A. Levy. "European Acid Rain: The Power of Tote-Board Diplomacy." Institutions for the Earth: Sources of Effective International Environmental Protection. Ed. Peter M. Haas and Robert O. Keohane. MIT Press, 1993. Print.

Manila Standard Today. "Asean Dared to Act on Myanmar." Manila Standard Today (Philippines) 7 Apr. 2005. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Mansor, Lokman. "PM: We Support Sanctions against Errant Members." New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia) 14 Jan. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Manthorpe, Jonathan. "Economic Club Opens Arms for Mynamar." Hamilton Spectator, The (Ontario, Canada) 7 Dec. 1996: D12. Print.

"NewsBank InfoWeb." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Parameswaran, P. "ASEAN Voices ‘Revulsion' over Myanmar Crackdown." Agence

France-Presse 27 Sept. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Peachey, Paul. "Thailand Faces Tough Questions but Likely to Escape Censure at ASEAN Summit." Agence France-Presse 23 Nov. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Peou, Sorpong. "The Subsidiarity Model of Global Governance in the UN-ASEAN Context." Global governance 4 (1998): 439. Print.

Purba, Kornelius. "Building ‘Non-Interference.'" WorldSources Online 15 Oct. 2003. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Ramcharan, Robin. "ASEAN and Non-Interference: A Principle Maintained." Contemporary Southeast Asia (2000): 60–88. Print.

Saengchan, Nattapol. "Undesirable Consequences of an ASEAN Peacekeeping Force." Jakarta Post 2 Mar. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Severino, Rodolfo C. "Sovereignty, Intervention and the ASEAN Way." ASEAN Scholars' Roundtable. Singapore. 2000.

Siangkin. "Is There a Lack of Focus in Indonesia's Foreign Policy?" Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 2 Oct. 2000: 44. Print.

"Manila to Invoke Principle of Non-Intervention." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 21 July 2000: 38. Print.

Singapore, Amy Kazmin in. "Asean Charter Falls Foul of Burma Divisions." Financial Times (London, England) 21 Nov. 2007. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Singer, J. David. "Reconstructing the Correlates of War Dataset on Material Capabilities of States, 1816–1985." International Interactions 14.2 (1988): 115–132. Print.

Singer, J. David, Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey. "Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 18201965." Peace, war, and numbers 19 (1972): n. pag. Google Scholar. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Stewart, Ian. "ASEAN Divides over Intervention Plan." Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia) 20 July 1998: 007. Print.

"Thailand | Freedom House." N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

The Straits Times. "Asean's Peace." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 8 Mar. 2004. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

"Thailand to Push for ‘Troika' Plan to Act in Crises." Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore) 19 July 2000: 30. Print.

The Washington Times. "Telling It like It Is to ASEAN." Washington Times, The (DC) 4 Aug. 1997: A18. Print.

Timberlake, Ian. "Southeast Asia Takes ‘Breakthrough' Step toward Regional Rights Body." Agence France-Presse 25 July 2005. Web. 13 Jan. 2015.

Torode, Greg. "Crisis-Hit Nations to ‘Usher in' New Order." South China Morning Post (Hong Kong) 4 July 1998: 11. Print.

"UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset." N.p., 2014. Web. 13 Jan. 2015. Wheeler, Nicholas J., and Tim Ddunne. "East Timor and the New Humanitarian Interventionism." International Affairs 77.4 (2001): 805–827. Print.

Endnotes

- Jonathan Manthorpe, “Economic Club Opens Arms for Mynamar,” Hamilton Spectator, The (Ontario, Canada), December 7, 1996, FINAL edition.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Vietnam Offers Refuge to Foreigners Fleeing Cambodia - Japanese Report,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, July 12, 1997, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0F99F5D92E430FE4?p=AWNB.

- Peter Alford, “Thais Push Radical Shift in ASEAN,” Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia), July 6, 1998, 1 edition.

- Peter Alford, “Neighbours Fear Burma,” Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia), July 10, 1998, 1 edition.

- Greg Torode, “Crisis-Hit Nations to ‘Usher in’ New Order,” South China Morning Post (Hong Kong), July 4, 1998, 2 edition.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Indonesia Opposes Changing ASEAN’s Nonintervention Policy,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, July 15, 1998, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0F98E44997028BED?p=AWNB.

- Ian Stewart, “ASEAN Divides over Intervention Plan,” Australian, The/Weekend Australian/Australian Magazine, The (Australia), July 20, 1998, 1 edition.

- “Thailand to Push for ‘Troika’ Plan to Act in Crises,” Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), July 19, 2000.

- “ASEAN Foreign Ministers Differ on Embracing Globalization Trend,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, July 25, 2000, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/0F97DCB197842F3A?p=AWNB.

- Ibid.

- Kim Chew Lee, “Potential for Action Shows There’s Life in Asean yet,” Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), July 24, 2000.

- Amy Kazmin, “Singapore Warns of North Asian Economic Threat: Asean Urged to Speed up Financial Reforms or Face Becoming ‘Irrelevant,’” Financial Times (London, England), July 25, 2000, USA Ed2 edition.

- Lee, “Potential for Action Shows There’s Life in Asean yet.”

- Ibid.

- “ASEAN Foreign Ministers Differ on Embracing Globalization Trend.”

- Siangkin, “Is There a Lack of Focus in Indonesia’s Foreign Policy?,” Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), October 2, 2000.

- Kornelius Purba, “Building ‘Non-Interference,’” WorldSources Online, October 15, 2003, http://infoweb.newsbank. com/resources/doc/nb/news/0FE3C061A81B689A?p=AWNB.

- Kim Chew Lee, “Peacekeeper Plan for Region Shelved - Jakarta’s Proposal Fails to Get Support from Its Partners in Asean Which Say It Is Too Costly and Premature,” Straits Times,

- The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), June 29, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/10382BB397AEEDE8?p=AWNB.

- “Undesirable Consequences of an ASEAN Peacekeeping Force,” WorldSources Online, March 2, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/101170A261AEB861?p=AWNB.

- “Asean’s Peace,” Straits Times, The (includes Sunday Times and Business Times) (Singapore), March 8, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/1012EE02450C0526?p=AWNB.

- Ibid.

- “Indonesian President Slams Unilateralism, Promotes Dialogue,” Deutsche Press-Agentur, June 30, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/1038A7DA897A2B9E?p=AWNB.

- “ASEAN to Reiterate Call for Myanmar to Increase ‘Democratic Space,’” Deutsche Press-Agentur, October 25, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/106D64150A9254A8?p=AWNB.

- “ROUNDUP: Singapore Concerned over Myanmar’s National Reconciliation Process,” Deutsche Press-Agentur, October 22, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/105E37BFA309C164?p=AWNB.

- “Malaysia Heads Calls for Burma to Be Barred from Taking over,” Financial Times (London, England), March 28, 2005, London Ed1 edition.

- “ASEAN Chief Doubts Influence of Malaysian Ultimatum on Burma,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, March 31, 2005, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/10934EBC704090A0?p=AWNB.

- Ibid.

- “Vietnamese, Burmese Leaders Discuss ASEAN, Regional, Bilateral Issues,” BBC Monitoring International Reports, August 11, 2004, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/1046D6F5B164ADEF?p=AWNB.

- “ASEAN Chief Doubts Influence of Malaysian Ultimatum on Burma.”

- Ian Timberlake, “Southeast Asia Takes ‘Breakthrough’ Step toward Regional Rights Body,” Agence France-Presse, July 25, 2005, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/10B982B862EE0058?p=AWNB.

- “Southeast Asia Lays Path for Future,” Iran News (Iran), January 14, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/ doc/nb/news/11C7824E0599DA68?p=AWNB.

- “ASEAN Official Complete Drafting of Landmark Charter,” Kyodo News International, Inc., October 22, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/11C774790F713388?p=AWNB.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Amy Kazmin in Singapore, “Asean Charter Falls Foul of Burma Divisions,” Financial Times (London, England), November 21, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/11D19704A8424E10?p=AWNB.

- Lokman Mansor, “PM: We Support Sanctions against Errant Members,” New Straits Times (Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), January 14, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/116B094433728070?p=AWNB.

- “Bold Moves Proposed to Prevent ASEAN from Atrophy,” Deutsche Press-Agentur, January 6, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/11683673268757A0?p=AWNB.

- “Vietnam Benefit from ASEAN’s Non-Interference Stance,” Bernama: The Malaysian National News Agency (Malaysia), January 27, 2007, http://infoweb.newsbank.com/resources/doc/nb/news/1182C0733A457EE8?p=AWNB.

Notes

- The ten countries are Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam.

- Conflict may have started or ended outside of this time frame

- This conflict is included because East Timor was Indonesia’s colony and ASEAN referred to this conflict as an internal issue for Indonesia (Dupont 163).

- Freedom House measures states’ political rights and civil liberties on a scale from 1 (most democratic) to 7 (least democratic).

- More details on the calculation method are given in Appendix A.

- More details on sources for Table 2 are listed in Appendix B.

- Data sources: GDP -“IMF DataMapper.”; Population - “Data | The World Bank,” accessed January 13, 2015, http://data.worldbank.org/; Military expenditures - J. David Singer, Stuart Bremer, and John Stuckey, “Capability Distribution, Uncertainty, and Major Power War, 1820-1965,” Peace, War, and Numbers 19 (1972), http://www.correlatesofwar.org/COW2%20Data/Capabilities/nmc4.htm; J. David Singer, “Reconstructing the Correlates of War Dataset on Material Capabilities of States, 1816–1985,” International Interactions 14, no. 2 (1988): 115–32.

Appendices

Appendix A: Confidence Scale Calculation

The Confidence scale measures ASEAN members' confidence that their sovereignty will not be subject to external interference. The first component of the index, democracy, is based on the Freedom House score of each country. Freedom House measures political rights and civil liberties of states, giving each country a score from 1 (most democratic) to 7 (least democratic). Here, this score is rescaled to fit the 0 to 1 scale and to vary in the same direction with the confidence level. For example, if a country's Freedom House score is 4 (like Indonesia in 1999), its Democracy index is calculated according to the formula below: Dem=(7-4)/(7-1)=3/6=0.5

The second component of the Confidence scale, relative power (RP), is estimated from three proxies: GDP, population and military expenditures.7 I calculate the GDP index (GDP) by dividing a country's GDP by ASEAN's total GDP of that same year. For example, in 2006, Thailand's GDP was 207.089 billion USD, while the total GDP of ASEAN was 1109.629 billion USD. Thus, its GDP index equals to 207.089/1109.629=0.187. The population index (Pop) and the military expenditures index (Milex) for each country are calculated using the same method with the GDP index. Because there has not been any dominant theory on which factor is more important to a country's relative power than the others, we distribute the weight equally for all factors. So the RP index is calculated using the formula:

RP=1/3×GDP+1/3×Pop+1/3×Milex

The Confidence scale of each country, which measures the country's confidence in its immunity against future ASEAN's intervention in the absence of the non-interference principle, is the weighted sum of the two components – democracy (Dem) and relative power (RP):

Confidence=1/2×Dem+1/2×RP

0≤Confidence≤1

Appendix B: Detailed Sources for Table 2

Table 2, showing cases when there were diverse opinions regarding the application of the non-interference principle from 1997 to 2007, is reproduced below with detailed sources for ASEAN members' positions in each case:

Image Attributions

By Gunawan Kartapranata (Own work) ASEAN Nations Flags in Jakarta 3.jpg 2011[CC-BY-SA-3.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ASEAN_Nations_Flags_in_Jakarta_3.jpg)], via Wikimedia Commons.

By Francois Polito (Own work) Manifestion pour la liberation de aung san suu kyi au siege de l ONU a new york.jpg 2003 [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Manifestion_pour_la_liberation_de_aung_san_suu_ kyi_au_siege_de_l_ONU_a_new_york.jpg)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

A large portion of Robert Nozick’s Anarchy, The State and Utopia is dedicated to refuting the theories of John Rawls. Specifically, Nozick takes issue with Rawls’ conception of distributive justice as it pertains to economic inequalities. Rawls wrote that economic inequalities should only be permitted if they are to the benefit of society, and especially if they are to the benefit of its least advantaged members; this has... MORE»

Economic regionalism has been an observable phenomenon worldwide. Many countries around the world pursue some degree of economic integration with neighbouring countries, in the hopes of capitalizing on the benefits of such an arrangement. At the turn of the 21st century, there already existed various regional economic institutions... MORE»

Regionalism, as Edward Mansfield describes, usually involves policy coordination through formal institutions within a region.1 Although there are conceptual debates surrounding what a region is and what regionalism is, empirically... MORE»

Myanmar, sitting on the border between South and Southeast Asia, reflects a historically oppressive state with internal struggle as surrounding countries compete for influence. In 1990, the government promised multi-party elections only to ignore the results and imprison advocates for democracy, including Aung San Suu Kyi, the face... MORE»

Latest in Political Science

2022, Vol. 14 No. 09

This interdisciplinary paper investigates the shortfalls and obstacles to success currently facing the climate movement, examining issues represented by the disconnect between policy and electoral politics, the hypocrisy and blatant indifference... Read Article »

2022, Vol. 14 No. 06

Two of the most prevalent protest movements in recent history were the Black Lives Matter and the #StopTheSteal movements. While there are many differences between the two, one of the most prevalent is their use of violence. Whereas the BLM movement... Read Article »

2022, Vol. 14 No. 05

Strong linkages between autocrats and the military are often seen as a necessary condition for authoritarian regime survival in the face of uprising. The Arab Spring of 2011 supports this contention: the armed forces in Libya and Syria suppressed... Read Article »

2022, Vol. 14 No. 04

During the summer of 2020, two fatal shootings occurred following Black Lives Matter protests. The first event involved Kyle Rittenhouse in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and the second Michael Reinoehl in Portland, Oregon. Two shootings, each committed by... Read Article »

2022, Vol. 14 No. 02

In popular international relations (IR) theory, knowledge production is often dismissed as an objective process between the researcher and the empirical world. This article rejects this notion and contends that the process of knowledge production... Read Article »

2022, Vol. 14 No. 01

This article explores the political relationship between nation-building, ethnicity, and democracy in the context of Ethiopia. It traces Ethiopia's poltical history, explores the consequential role ethnicity has played in the formation of the modern... Read Article »

2022, Vol. 14 No. 01

The study examines the degree to which Xi Jinping has brought about a strategic shift to the Chinese outward investment pattern and how this may present significant political leverage and military advantages for China in the Indian Ocean Region (... Read Article »

|