From Cornell International Affairs Review VOL. 1 NO. 2U.S. Policy Towards Colombia: A Focus on the Wrong Issue

By

Cornell International Affairs Review 2008, Vol. 1 No. 2 | pg. 1/1

KEYWORDS:

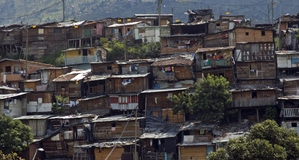

In recent years the United States has undertaken daunting activities in fighting two overarching wars against intangible enemies across many borders. The war on drugs and the war on terror have severed many national ties, even as globalization continues. Only a few countries, however, have experienced the full devastation of both of these wars simultaneously. Colombia has been the epicenter of the war on drugs and is considered a crucial front in the war on terror. The politics within Colombia have been profoundly affected under the constant watch of the United States. Much of the recent policy in Colombia has focused on the wars on drugs and terror to appease America and its leaders. In light of all this effort, little has fundamentally changed. Colombia, though its famous Medellín and Cali drug cartels have fled, remains a haven for coca cultivation and home to many violent paramilitary and guerrilla groups who frequently spread violence throughout the country. The United States has focused heavily on drug politics through the injection of military aid and arms. The biggest fault in this political tactic is that arms only continue to fuel the already-problematic violence across the Colombian countryside. This presents a paradox in American foreign policy that demands the attention of the international community. Issues of globalization, illicit trades, and violence are extremely important to international politics. Colombia, as one of the oldest democracies in the western hemisphere, plays an important role in the politics of Latin America and the world. Colombia is currently working towards a free trade agreement with the United States as a means of bettering its infrastructure to further combat issues of drugs and violence. Colombia’s strategic location, bordering both the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean while being close to the Panama Canal, makes its politics important to United States and the western hemisphere. Last, the presence of drugs and arms in the world economy is extremely destructive to the people living in affected areas. The important problems that Colombia faces have been present in Latin America for a long time, although Colombia’s history with drug cultivation, trade, and violence is relatively young. The drug trade started to affect Colombia only in the 1970s as Bolivian and Peruvian traffickers utilized routes in the country for transporting drugs. As a result of counternarcotics efforts in Bolivia and Peru, production within Colombia started to accelerate. By the 1990s, Colombia provided as much as 90% of the cocaine consumed in the United States as well as a significant portion of heroin.1 It was also at this point that the paramilitary groups began to take their current shape, with extensive growth in the 1980s and 1990s. The growth of the paramilitary groups resulted in an expansion of the illicit arms trade, since these organizations were the primary users of such weapons. Due to the growth of both the arms and drug trades in the last two decades of the 20th century, they became increasingly intertwined. This relationship between the two trades is crucial to understanding both the problems of U.S. foreign policy in Colombia and Colombian domestic policy. Although little research has been done in regards to this relationship, it is still quite strong. For example, Colombia is one of the leading recipients of U.S. military aid as a result of efforts to combat drugs. Furthermore, many arms in Latin America enter the illicit markets via legal military transactions followed by illegal sales conducted by military personnel. Colombia is also among the least-active opponents of small arms in its region, leading to fewer restrictions than its neighbors. It is one of the few nations in the Americas to not keep detailed records of holdings, transactions, and transfers of small arms and light weapons as of 2006.2 Colombia, with U.S. assistance, has shown equally poor control over the illicit narcotics trade. Even efforts to fumigate coca crops have been unsuccessful in bringing the cultivation back to the levels of the 1980s.3 The 2007 International Narcotics Control Strategy Reports (INCSR) from the U.S. Department of State showed significant increases in eradication efforts especially between 2004 and 2006, while drug cultivation rose to 144,000 hectares from 114,000 the year before.4 Failed attempts at controlling the trades and continued growth of the trades are commonplace in Colombia. Colombia’s guerrilla and paramilitary groups play an important role in the trades as well and lead to further connections between drugs and arms. The guerilla groups, especially, have experienced massive growth in recent years. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the largest of the organizations, has expanded from 3,600 members in 1987 to roughly 20,000 on more than 105 fronts, covering over 40% of the country in 2004.5 Their relationship to the drug trade remains somewhat unclear, although it is apparent that even on the most optimistic level, revenue is being made from the coca crops and is further being used to fortify their military machine. It is also fairly clear that the drug trade has added stronger enemies for the FARC and other guerilla groups in the form of the Colombian and United States militaries. The existence of these enemies has increased the need for arms in disputed territories, leading to another tie between drugs and arms. One trend that has also become abundantly clear is the increased quantities of arms purchased by FARC, other guerilla groups, and the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC—the primary paramilitary group). Historically, these groups avoided bulk purchases to avoid attention; however, this has begun to change due to increased requirements when fighting the U.S.-supported Colombian forces.6 The non-state actors in Colombia provide an additional set of connections between the cultivation of drugs and the trade in illicit arms. Despite the strong ties between the two trades, the United States, a crucial player in nearly all international relations, has taken some steps towards the eradication of drugs in Colombia while not paying much attention to the issue of arms. Plan Colombia is the embodiment of this narrow focus on narcotics. The initial proposals for the legislation by Colombian President Andrés Pastrana in 1998 called for international aid for a variety of investments in social development as a means of reducing crime and bettering the overall sociopolitical sphere within the country. The primary means for meeting such goals involved the subsidized replacement of crops for small cultivators of coca as well as extensive peace negotiations. However, the legislation quickly became altered by U.S. views to focus on counternarcotics through high levels of military aid. This updated policy, which received little media coverage and was not even available in Spanish when first introduced, was approved by the United States Congress with $860 million initially dedicated to military aid.7 Colombia created and trained a highly-mobile military force meant for counternarcotics across the Colombian countryside. Plan Colombia also called for aerial fumigation of drug crops as an important part of the legislation. The fumigation, which has been occurring since the 1980s (originally for marijuana crops), has failed to reduce the number of crops, and remains dangerous to the farmers exposed to the chemicals. Furthermore, coca cultivation is a highly mobile business often characterized by a ‘balloon effect,’ in which the elimination of one area of growth results in the creation of another. The United States has continued its financial support for the Colombian counterinsurgency and counternarcotics efforts, although they are quite different from the initial goals put forward by the Colombian government. The efforts of the United States government show its narrow understanding of the issues in Colombia. Legislation has consistently chosen to focus on the issue of drugs while adding arms to the country, which has in turn led to more violence and human rights violations. This is where the paradox in US policy lies. The situation in Colombia is devastating for those who must live with it day-to-day. The United States, while focusing on its own goals, has used its ability to throw its weight around in such a way that has left the Colombian government with little say in its own domestic politics. The focus on counternarcotics through a series of military endeavors has done little to solve the sociopolitical problems and has in fact increased other harms, such as the violence caused by armed conflicts. The reasons for such a counterproductive set of policy goals remain unclear, but must be acknowledged. Though many possible policies could be beneficial to the Colombian situation, the most successful are likely to come in the form of social policies. Alternative development is likely to be the best policy to help Colombia. This policy calls for viable options outside of the narcotics industry for farmers and individuals who have had few other possibilities in the past. Attempts so far have not been overarching or permanent enough. Examples include short-term construction, and manufacturing that has had little demand for the products. Alternative development must create long-term jobs, be involved in a growing inudstry, and be properly financed. Alternative development could also be beneficial to the other problems that plague Colombia. In the case of arms, alternative development would provide work to individuals who previously required arms for protection in the drug industry. Furthermore, the switch to other forms of work is likely to severely curb narcotics cultivation and therefore reduce the ability of insurgent groups to purchase arms. Alternative development, however, is not likely to be the sole solution to Colombia’s problems. Peace negotiations should be paired with these alternative development policies. They too are likely to help multiple facets of the Colombian problems. While directly opening up discussion for the insurgent groups, hopefully leading to lessened violence, they should also assist the arms situation. The reduced focus on military action would slow the interior arms race that has been occurring throughout the country. Peace negotiations with U.S.-support would likely grant needed authority to the Colombian government as well, therefore strengthening the country’s institutions. Peace negotiations have been attempted in the past, but without proper support domestically and internationally, they have not been successful. The situation in Colombia is extremely complex, and there is no set of solutions that will solve every problem. However, alternative development, peace negotiations, and most importantly a reduction of the focus on militarized action will help. Colombia needs a lot of assistance in its efforts to reduce violence, drugs, and arms, but these policies can help to achieve such goals. The United States must recognize this fact and act accordingly; otherwise, the problems will continue to worsen. Endnotes

Suggested Reading from Inquiries Journal

Inquiries Journal provides undergraduate and graduate students around the world a platform for the wide dissemination of academic work over a range of core disciplines. Representing the work of students from hundreds of institutions around the globe, Inquiries Journal's large database of academic articles is completely free. Learn more | Blog | Submit Latest in International Affairs |